Why Not Start with Dignity

Jeffrey Mensendiek serves with J.F. Oberlin University in Tokyo, Japan.

The once postponed 2020 Tokyo Olympics begins today. The government had hoped that things would improve by now, but here we are with our fourth Emergency Declaration in Tokyo, and with the high number of people contracting the virus rising each day. The government has decided not to allow people into the venues to cheer on the athletes. Meanwhile, the Japanese people are tired of the repeated measures taken to try to keep the pandemic from getting out of hand. Many are angry that the government misjudged the risks by favoring political and business interests, some question why it is taking so long for Japan to get the vaccine in the first place, and 55% of the public believe we ought not to hold the Olympics at this time. It feels like we are headed into a train wreck. Our hospitals are already running at full capacity, and experts are worried about what August will bring. The only one with a smile on his face is Thomas Bach (President of the International Olympic Committee) who said to the prime minister, “Maybe if the number of people contracting the virus goes down some venues can be opened to the public.” He also promised that no risks would be posed to Japan by hosting the Olympic athletes. However, Bach’s statements reveal just how out of touch he is with the sentiments of the common people, and with reality itself.

For the past sixteen months, I have been teaching my university classes online. Zoom has become my channel to connect with the outside world. I hold meetings, workshops, connect with friends and family, all on Zoom. On the days that I do go to work, I can spend the whole day without talking to anyone. My family has become my social bubble, and all other socializing has been limited to the computer screen. Our family has recently moved into a new neighborhood in Yokohama, but we have yet to have anyone over to see our new place.

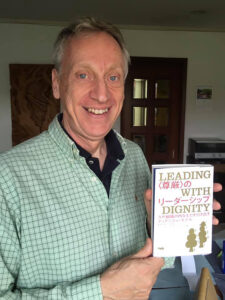

In the meantime, my wife Kazuko and I have been translating a book on dignity into Japanese. The book is called “Leading with Dignity,” and was written by a Harvard scholar (Donna Hicks) who has been involved with conflict resolution around the world. Her book 1) helps people see what dignity looks like in everyday life, 2) shows the temptations we all face to violate dignity, 3) outlines the skills needed to protect the dignity, and 4) provides living examples of communities, schools, and organizations in the US that are trying to create “cultures of dignity” where people can feel safe to be their true selves without fear of judgment or retribution. As the author says, it is a how-to manual for anybody who wants to learn how to protect dignity in their everyday lives.

I am presently involved with a small Christian NGO called the Asian Christian Education Fund (ACEF) that has been involved for the past thirty years in providing elementary school education for children of low-income families in Bangladesh. ACEF has organized study tours for young people to expose them to the harsh realities in Bangladesh, but now with the pandemic, these activities have been put on hold. This year ACEF adopted “dignity education” as one of their main activities for outreach within Japan. With the Japanese translation of “Leading with Dignity” hot off the press, I am set to offer dignity workshops to equip my ACEF colleagues and young leaders with the tools for dignity education. Many of my colleagues are teachers in the various Christian schools around the country. The good thing about dignity is that it has no borders. It doesn’t ask which group you belong to. Neither does it judge you by the color of your skin, your gender, or age. It applies to everyone, and it is our common and collective responsibility to make sure that we uphold the dignity of all living things. As the author says; “leaders are the guardians of dignity.” I am hoping that my colleagues and I can create a new dignity curriculum and some innovative teaching materials to help future leaders with the tools to lead with dignity.

Two such leaders are a couple named Maya and Tashi who have been fighting in the courts over the right for married couples to maintain separate surnames if they so choose. Just recently they lost their case in the Supreme Court but they say that their fight has only just begun. I have known the two of them since they were college students. They joined me on separate study tours (one to Bangladesh and one to India) where we had the opportunity to meet people of different religious traditions working together in the spirit of mutual trust and respect. Maya is a Christian, and Tashi is a Buddhist priest. I like to think that their exposure to living examples of inter-religious trust and respect helped them in their commitment to a shared life together. Religious differences are often seen as a force that divides people. Likewise, couples who maintain different surnames may be seen by traditional society as disruptive of the family unit. I believe, however, that if we are grounded on the firm bedrock of dignity, nothing can separate us from one another. It’s about time that we take a hard look at what dignity is. As Hicks says, although everyone is born with dignity, that doesn’t mean that we know how to act like it. Dignity has to be learned. So why not start from the beginning to learn about the role dignity plays in our lives. I am hoping that our translation of the book will inspire many more future leaders like Maya and Tashi.

Jeffrey Mensendiek serves with J.F. Oberlin University in Tokyo, Japan. His appointment is made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, and your special gifts.