But This Is Your Country!

Written by Nishan Bakalian, serving in Lebanon with the Union of Armenian Evangelical Churches.

Perched atop a barstool outside a one-table “manoucheh” (the standard Lebanese breakfast food – pizza-shaped dough with thyme and oil topping) bakery, I was enjoying breakfast late one morning on Armenia Street in Beirut. A young couple with their toddler in a stroller walked up. The husband entered the shop and placed their order in Arabic, and then, standing right next to me, they began discussing something. The wife was busy mixing formula for the baby, freely making use of “my” table to do so (an American interpersonal distance measurement). Meanwhile, my Lebanese and Armenian nosiness piqued, and I started paying unconcealed attention to the scene unfolding at my front-row seat. He, Lebanese, she, Filipina, were glancing back and forth from one cell phone to another and discussing their next move in somewhat heated English. He: “I don’t know, it’s been four years since I’ve been here! A lot has changed, you know.” She: “I don’t mind walking, but you have to figure out where we’re going! It’s your country!”

I waited until I could catch both of their eyes, or perhaps all four, and asked, “Can I be of help?” With little hesitation, they said that they were looking for places that might have artwork on display, and maybe some things for sale as well. I said, “Just ahead of you, on the other side of the street, is ‘Plan Bey.’ I think it’s what you’re looking for. Plus, if you walk back to Gemmayzeh, stay on the left fork, with the traffic coming to you, there are a few places there as well.” Obviously relieved, the wife exclaimed, “Thank you! You saved us from an argument!”

The husband darted in and came out with the manoucheh and asked, “Is there an exchange place nearby?” I said, “You can stop at any money transfer place.” “They exchange money?” “But it’s not worth the trouble. Just about every business will accept payment in US dollars.” “But I’ve heard that some places don’t have good rates.” “As long as it’s 89,000-something lira, the difference won’t be much. Don’t worry about it.” As they prepared to leave, the husband said, “You should start a blog!” I smiled and said, “I have one already!” and then spelled out “Nshanakir” for him. “There it is, the first hit.” And he started reading it as they went ahead to their first destination.

Living and serving in Lebanon is like this. It is both “our” and “not our” country. We see the actions of the political class stalling the election of a president for the past year, and the lifestyles of the privileged class maintaining their happy lifestyle and feeling anger at what they are doing to our “home.” Though we do not directly feel the pain of those around us, we still are pierced by the tales about families in our churches and schools, tales of woe, economic and social, related by our co-workers. We do our best to listen well and support them without pretending that we are in the same boat.

Apparently, native-born Lebanese also have difficulty considering their country “theirs,” but in a different direction. They both love and hate their country; they run away from it and return to it. While they are in Lebanon, they curse its condition, and when they are on distant shores, they cannot but extol its charms. As Maria continues her efforts at Haigazian University in the Alumni Affairs office, making contacts and preparing e-newsletters, she has noticed that there are some graduates who feel an intense connection and even obligation to the university, and many others who consider it “no longer of interest to me.”

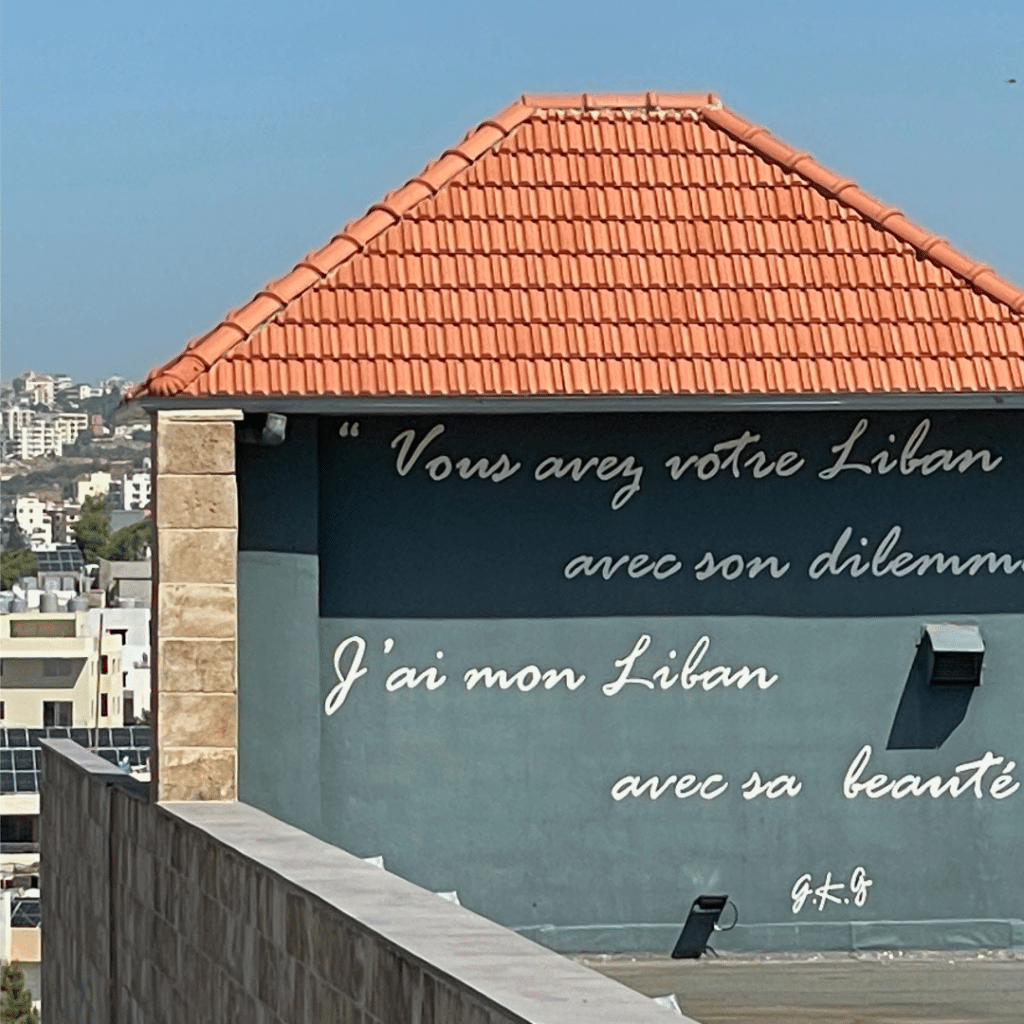

Seeing such conflicting connections and puzzlement over people’s sense of belonging, we detect that it has involuntarily become part of our makeup as we serve here and “seek the welfare of the city” (Jer. 29.7) to which God has sent us. Since living in the Middle East means reconciling and coexisting with the layers of history that surround us, as Armenians, we have an added layer weighing on our hearts. With sorrow and shame, we are witnessing, albeit at a distance, the ongoing dismemberment, displacement, and destruction of Armenian homelands. We cannot help but be paralyzed by the unfolding scenes of deprivation and military actions against the native population of Artsakh (or Nagorno-Karabakh) since the 2020 war up to and beyond the current surrender. That country, too, is “ours”, although Azerbaijan, like its sister Turkey, does its utmost to deny it, resorting to physically chiseling away any evidence of the Armenian presence in the land and spreading historical disinformation to the world while claiming to have the welfare of the Armenian population in mind – those whose food, medicine, electricity, and communication they have been blockading since last December.

Yet this head-spinning pain we are enduring may be one of our most important resources in ministering in this region in these days. Though it is not a tool one would actively desire, when we are in God’s hands, it shapes us to think, feel, pray, and act in a Christlike manner. It brings us to a place of interaction with beloved friends and strangers nearby, with suffering compatriots only a short distance from us, and with caring partners half a world away. Since Christ Jesus endured such trials (I Peter 4.13), these ordeals bind us together across borders into ever closer fellowship, warn us away from becoming the callous and cruel of this world, and enable us to reflect Christ’s compassion, wisdom, and courage as we continue to labor in his Name. So, we can confidently call the place we came from, the place we serve, and all the places whose sorrows we daily bear – “our country.”

Rev. Nishan Bakalian

Make a gift that supports the work of Nishan and Maria Bakalian