Fall In or Let Go of the Nets

Jonah 3:10; Mark 1:14-20

“If you become a fish in a trout stream, said his mother,

I will become a fisherman and I will fish for you.”

This is my call story plain and simple. It is also one of the stories in Margaret Wise Brown’s children’s book, The Runaway Bunny which I read to my daughter Colette, religiously alternating with Brown’s other book, Good Night Moon. Both books allow for imaginative add-ons like “Good night dust under my bed”, and “If you become a mouse, I will become a piece of cheese so I can live inside you.” These are the ones I can remember.

God’s call is like this, both inescapable and strangely comforting. Our lectionary readings this evening are good illustrations of God’s insistent and persistent call for us. After all we have been named already as God’s Beloveds. However, I am not sure comforting is the word either Jonah or the fishermen would use to describe this call to become part of God’s redemptive plans.

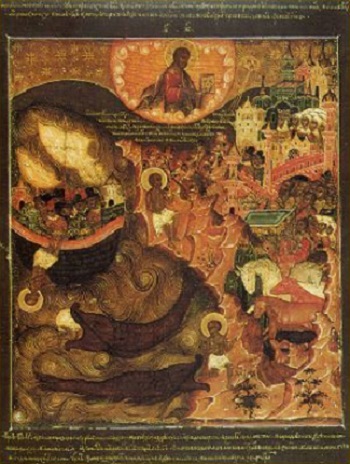

This is especially true for that reluctant prophet Jonah. In the Book of Jonah, the shortest book in the Bible, Jonah’s choice is to redeem a reviled people or drown. Jonah is remarkable among the prophets because his resistance to proclaiming the word of Lord comes from not wanting to let go of his righteous anger at the people of Nineveh because they were his enemies; they had destroyed his people He was worried that if he went to preach repentance that God might indeed forgive them. He feared he would succeed and his enemies would be saved.

So because he thought he could escape God (like the runaway bunny) he ran to Joppa (Jaffa) and bought a ticket on a boat to Tarshish (a city in Spain), as far away as possible from Nineveh (modern day Mosul in Iraq). He thought God was limited to his tribe, his land, and wouldn’t find him.

Once on board the ship, a big storm blew up frightening all the passengers. They believed that it came because the gods were punishing them for someone’s sin. Jonah confessed he was the one running from his God so he told them to dump him into the violent sea.

Once in the sea God swallowed him in the guise of a big fish which now most think of as a whale. Jonah was inside the whale for three days until he finally faced the fact there was no escape from God; then he began to sing to God. Three days in the belly of the beast makes Jonah an archetype for Jesus which is one of the reasons Christians love the story of Jonah; this plus the fact that he willingly sacrificed himself by throwing himself overboard.

Once Jonah repented for running away, the great fish (God?) spit him out. Then God called him a second time to go and preach repentance–our lesson today. This time Jonah obeyed God’s orders and wandered around the evil city of Nineveh repeating, “In 40 days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown.” And to Jonah’s surprise and dismay, the people listened and turned toward God. They put on sackcloth and fasted, and most importantly had a change of heart.

Instead of rejoicing, Jonah clung to his fear, to his anger and bitterness, to his prophetic indignity, to his hatred of his enemies. From the beginning to the end, he still couldn’t let go. He didn’t seem to have learned anything from his drowning in the sea nor his three days in the tomb of the whale’s belly.

Thus far in our story, it is Nineveh, the imperial capital of Assyria, who exercises the freedom of repentance. As theologian Bill Wylie-Kellermann says, “They match the solidarity of sin in violence with the solidarity of freedom in repentance. Here is an ironic tale bigger than the whale. Of course the final freedom is God’s–who also repents of anger in judgment.” We have a God who can repent.

I would like to interject here an interesting fact, a piece of good news. This year in Nineveh, Mosul, Iraq, Muslims and Christians celebrated Christmas at St. Paul’s Church because IS had finally been driven out. The Muslims helped the Christians rebuild their church in time for the Christmas holidays.

They celebrated their liberation and freedom to worship again by doing it together. Is this not the true sign of Jonah’s blessing? God’s inclusive love made manifest in God’s restored community?

Back to the story. Jonah struggled with his call to participate in God’s call for mercy and forgiveness. He struggled to accept a God that lives beyond borders and the land of his tribe; one who chooses to forgive and love even the enemies of his chosen people. Jonah is dumped in the sea to learn a lesson about the nature of God’s universal love and the eternal back and forth relationship between repentance, forgiveness, and love.

It’s easy to make fun of this reluctant prophet who holds onto his anger like a life jacket. But are we any different?

Most of us are prepared to denounce governments who pass laws that protect the rich and rob the poor but are we ready to sacrifice our financial privileges to help create a more equitable economic or social system?

We might be prepared to denounce companies who profit from other people’s oppression, who are breaking international laws, but are we willing to do without their products? Are we willing to sacrifice? Be banned for our beliefs?

It’s easy to point out the inhumanity of building a wall that separates families and farmers from their vineyards, and which allows others to steal land that doesn’t belong to them, but are we willing to build bridges between people so all can live together? Like Jonah, are we ready to let go of our indignation and allow repentance and change to really happen?

I love the story of the Runaway Bunny and Jonah because I think we are all a little afraid of God’s call. And I think we are also strangely comforted that no matter what happens to us including drowning, God will shape shift to find us and hold us even in the belly of a whale. And most importantly, God will give us a second chance.

I love the story of the Runaway Bunny and Jonah because I think we are all a little afraid of God’s call. And I think we are also strangely comforted that no matter what happens to us including drowning, God will shape shift to find us and hold us even in the belly of a whale. And most importantly, God will give us a second chance.

This story of Call is so different on the surface from the call of the disciples on the Sea of Galilee, not far from here in Capernaum. In Mark’s Gospel story, the fishermen immediately drop their nets and follow Jesus without a moment’s hesitation. Unlike Jonah holding onto his righteous anger, these exploited fishermen from Capernaum have nothing to lose and everything to gain by joining a movement of resistance. Yes, resistance. This is what Jesus was calling them to do when he says I will make you fish for people. It doesn’t mean to save souls. Jesus knew the prophetic literature of his day and sought to employ it anew. He was summoning these marginalized workers to join him in “Catching some big fish” to restore God’s kin-dom. The fishermen had to drop all their nets–business as usual and the debt systems that enslaved them. They had to cut off everything that tied them to life under Roman Occupation. Letting go was their repentance.

The call to discipleship, like the prophetic call, demands immediacy. It demands we stop and turn around, lose everything and risk going in a new direction. This is the scandalous freedom of answering the call.

I invite you this evening in this lovely restored chapel on the Sea of Galilee to ponder for a moment what new direction God might be calling you to follow. I invite you to reflect on what forces might be holding you back from moving forward. What righteous attitudes do you need to let go of in order to participate in God’s economy of grace?

Just like your baptism, I invite you to fall into the waters of life whether you know how to swim or not. I invite you to allow yourself to drown in God’s all-encompassing turbulent love, to even allow yourself to be swallowed up. I invite you to let go of all those tangled nets and say yes to God’s redemptive plan. Answering this call will cost you everything.

I leave you with Jonah’s Blessing from Jan L. Richardson:

It comes as a small surprise

that you would turn your back

on this blessing

that you would run

far from the direction

in which it calls.

That you would try

to put an ocean

between yourself

and what it asks.

Something in you knows

this blessing could

swallow you whole

no matter which way

you turn.

Hard to believe, then,

that every line of this blessing

swims in grace—-

grace that in the end,

even you

will find hard to fathom

so swiftly does it come

and with such completeness

encompassing all

it finds.

What to do, then,

with such a blessing

that depends so little

on us

yet asks everything?

What do to with a blessing

that comes with

such strange provision,

every inch of it

looking like something

that will draw us

into our dying?

Trust me when I say

all it wants

is for you

to fall in,

Aand let yourself

Be engulfed within

the curious refuge

that it holds.

And then to go

in the direction

it propels you

following its flow

that will bear you