The Right to Work: A Paradigm Shift

In December, Melel Xojobal hosted the Second National Child Workers Retreat in San Cristóbal. My team of three had spent the weeks before the retreat in helpful but harried preparation. While we were still spending half our day working in markets around the city like normal, the other half of the day was jam-packed with planning activities for the retreat.

We were reserving restaurants and event spaces, coordinating permission slips and release forms, and booking flights for the groups of child workers and adult collaborators from Mexico City, Oaxaca, Guadalajara, Veracruz, and Guatemala. Alongside these visiting groups, the retreat would be attended by children and adolescents from Melel Xojobal’s programs in San Cristóbal.

We were reserving restaurants and event spaces, coordinating permission slips and release forms, and booking flights for the groups of child workers and adult collaborators from Mexico City, Oaxaca, Guadalajara, Veracruz, and Guatemala. Alongside these visiting groups, the retreat would be attended by children and adolescents from Melel Xojobal’s programs in San Cristóbal.

The lack of sleep and weeks of hard work were all worth it for the three days that we spent at this retreat. The children drew pictures to detail the ways they exist in the world, paying special attention to both risk factors and protective factors that they face as children who work. We discussed the similarities and differences between their experiences, considering the differences in their ages, genders, type of work, and location. We realized that despite these differences, they could relate to each other’s life experiences as child workers. We also played soccer and had hula hoop relay races. We sang songs, acted out plays, roasted marshmallows, and told scary stories around a bonfire. We had a cultural night, where children from each region shared their unique traditional foods, sweets, songs, and dances. And we ended the weekend with a march and public demonstration in downtown San Cristóbal, calling attention to child workers’ rights.

There are moments from this weekend cemented in my mind. For example, when I walked into the dining room at dinner and saw the group of 10-year-olds that I work with at the markets yelling my name and wildly gesturing me over, pointing to the space that they had saved for me at their table. Balancing a mug of coffee, I received a line of soft hugs and “Buenos días, Abi!” our breath visible in the cold mountain air. Marching down the main street in San Cristóbal, we chanted and sang, refusing to let child workers be erased from public spaces.

There are moments from this weekend cemented in my mind. For example, when I walked into the dining room at dinner and saw the group of 10-year-olds that I work with at the markets yelling my name and wildly gesturing me over, pointing to the space that they had saved for me at their table. Balancing a mug of coffee, I received a line of soft hugs and “Buenos días, Abi!” our breath visible in the cold mountain air. Marching down the main street in San Cristóbal, we chanted and sang, refusing to let child workers be erased from public spaces.

One afternoon, the kids screamed with laughter as we played a game of freeze tag. Before starting this game, we explained that each person would be playing a role. All the children were cast as “Child Workers.” The adults were split into two groups. Those who could freeze the children wore labels including “Capitalism,” “Colonialism,” “Social Cleansing,” and “The Patriarchy.” The adults who could unfreeze the children were given roles like “Dignified Work,” “Play,” “Human Rights,” and “Organized Child Workers.” After we played, we sat in a circle, and the children reflected on how this game mirrored their own lives. We discussed how they, as child workers, could be frozen and halted by capitalism, colonialism, social cleansing, the patriarchy, and other forces. Then we talked about how their strategies against these forces include human rights, dignified work, playing games, and organizing together.

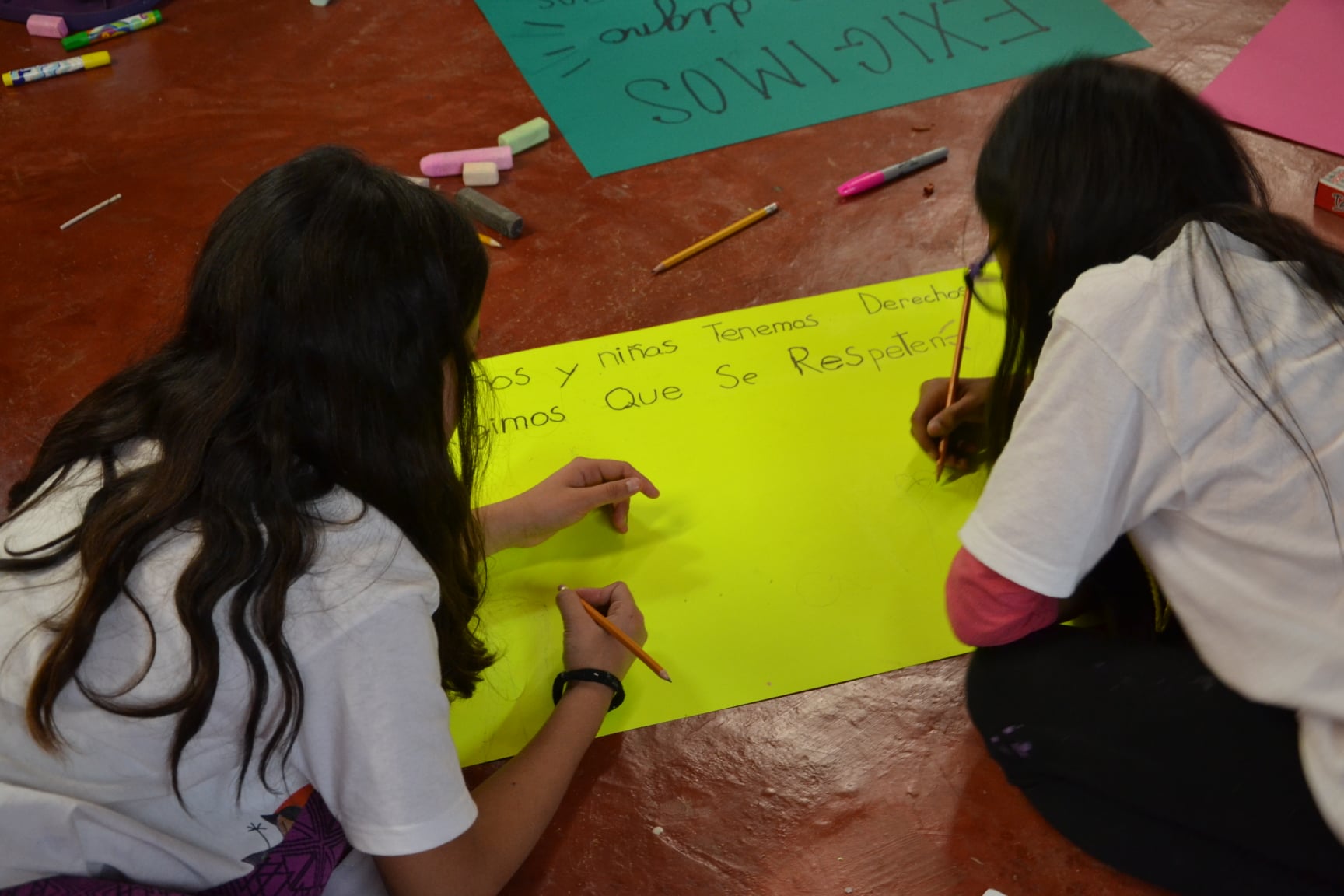

The night before the march, I sat with a few of the younger girls as we made posters to carry the next day. “What should I write?” one asked me. “Think of it like this,” I replied. “There are going to be people in the street tomorrow who don’t know anything about you and don’t know anything about this retreat. What do you want them to know about you, about us, or about child workers?” They all sat, thinking for a moment, then diligently

The night before the march, I sat with a few of the younger girls as we made posters to carry the next day. “What should I write?” one asked me. “Think of it like this,” I replied. “There are going to be people in the street tomorrow who don’t know anything about you and don’t know anything about this retreat. What do you want them to know about you, about us, or about child workers?” They all sat, thinking for a moment, then diligently

picked up their posters and markers and got to work. Slowly and painstakingly, messages appeared on these poster boards. “Exigimos que nos traten con respeto y humildad,” one wrote. “We demand that you treat us with respect and humility.” “Las niñas y los niños tengan el mismo derecho a trabajar,” another proclaimed. “Children have the same right to work [as adults].” “Exigimos espacios seguros para las niñas, niños, y trabajadores adolescentes,” wrote a third. “We demand safe spaces for child and adolescent workers to work.”

Six months ago, I thought that children should not work. I thought that child labor was, as a rule, wrong and immoral. I certainly never thought I would be at a retreat with smart, thoughtful, determined children, or that I would be marching with them in defense of their right to work.

There’s a lot to know about this issue, and much that I am still learning. I’m learning about the difference between safe, dignified work and exploitation. I’m learning that school and work are not mutually exclusive, that children can be both passionate students and diligently work afternoons and weekends with their families. I’m learning about the indigenous worldview, and how in indigenous communities, working alongside one’s family is an integral component of being a part of the family. I’m learning about the systemic oppression of child workers by local and national governments. And I’m learning about the complexities and realities these children and their families face each day.

As is so often the case, the more I learn, the more questions I have. I’ve been forced to reconsider things I thought I knew, and to confront and acknowledge the ways my own culture has shaped my beliefs and priorities. If anything, my first six months as a Global Mission Intern has made me painfully aware of how much I don’t know. But perhaps this is the greatest lesson that I’ve learned so far that all I can hope to do is keep an open mind, ask questions, and be ready to learn.

Abi Fate serves with Melel Xojobal, Mexico. Her appointment is made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, WOC, and your special gifts.